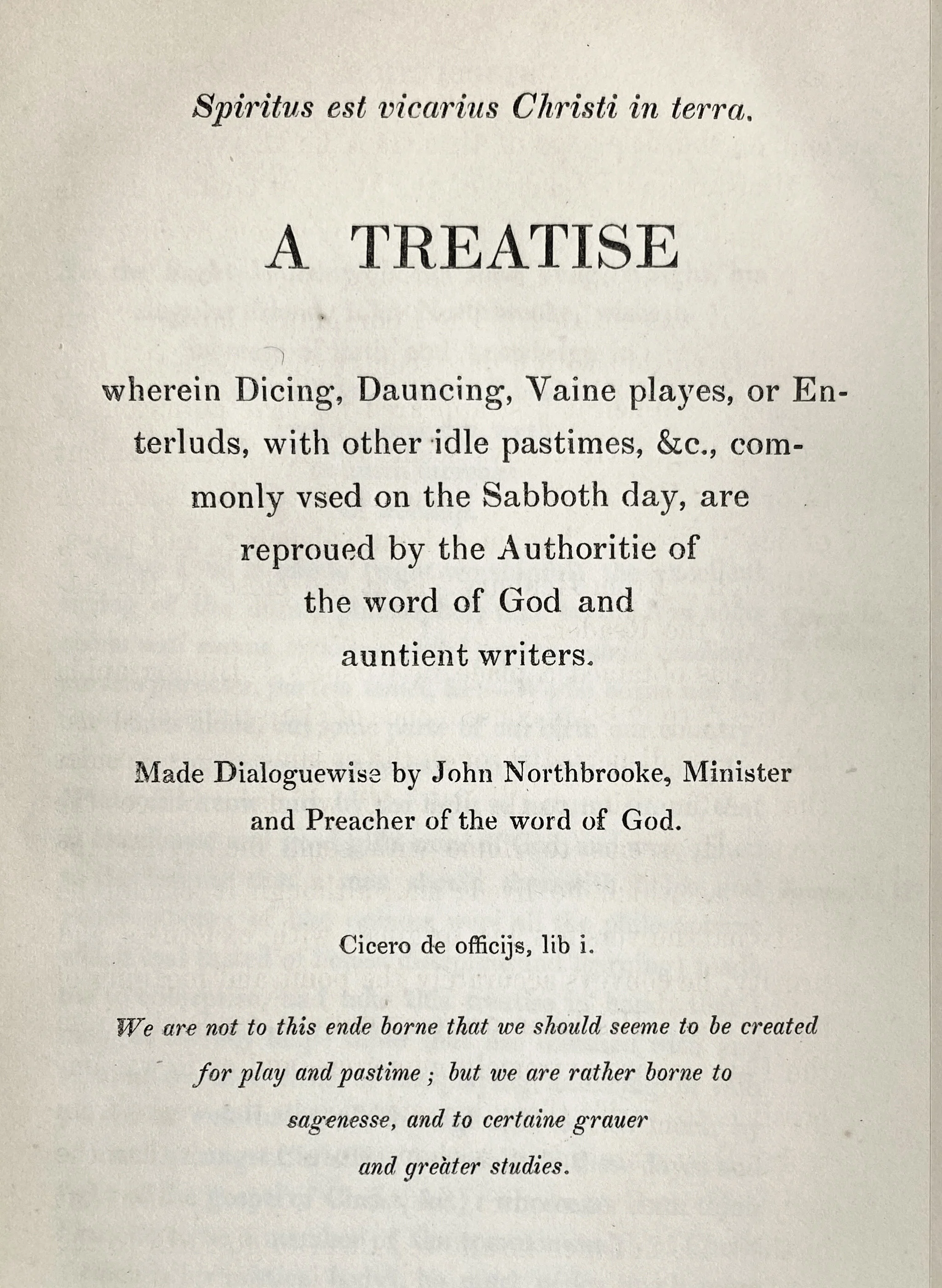

A Treatise Against Dicing, Dancing, Plays, and Interludes, with Other Idle Pastimes,

John Northbrooke, 1843 (first published 1577)

In the Portico Library’s 1818 edition of the Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth, biographer Lucy Aikin reports that “Elizabeth would recreate herself with a game of chess or… cards or tables*”.

Meanwhile, during Elizabeth’s reign, senior Bishops such as John Northbrooke were denouncing games, dancing, and pastimes as against “the word of God”.

*Tables: a board game similar to backgammon, developed from ancient games like senet

Memoirs of Lady Fanshawe,

Ann Fanshawe, 1829 (originally written in 1671)

A century after Elizabeth’s time, Ann Fanshawe wrote a detailed account of life in Spain, where her husband was Ambassador after the end of Puritan rule in Britain. During that time, “spectacles of pleasure” had been banned under laws against “lascivious mirth and levity”.

While staying in the Alcázar of Seville, the Fanshawes “were every day entertained with a variety of recreations; as shows upon the river, stage plays, dancing, men playing at legerdemain*…"

*legerdemain (literally light-of-hand in French): conjuring tricks

The Works of Thomas Middleton,

Thomas Middleton, 1814 (first published 1599-1627)

A Game at Chess premiered at the Globe Theatre in London in 1624. It was shut down after just nine days for satirising the failing diplomacy of King James I during Britain’s conflict with Spain. In this illustration, the Black Queen is modelled after Infanta Maria Anna of Spain and the White Queen after James’ daughter, Elizabeth Stuart. The playwright tried to use the allegory of chess to avoid directly mentioning individuals, but was censored anyway.

Theatre scholar Musa Gurnis has written that the play actively encouraged anti-Catholic persecution in England, but that the religious diversity of its 17th-century audiences was “far more nuanced than the too-often utilized binary of Protestantism and Catholicism”.