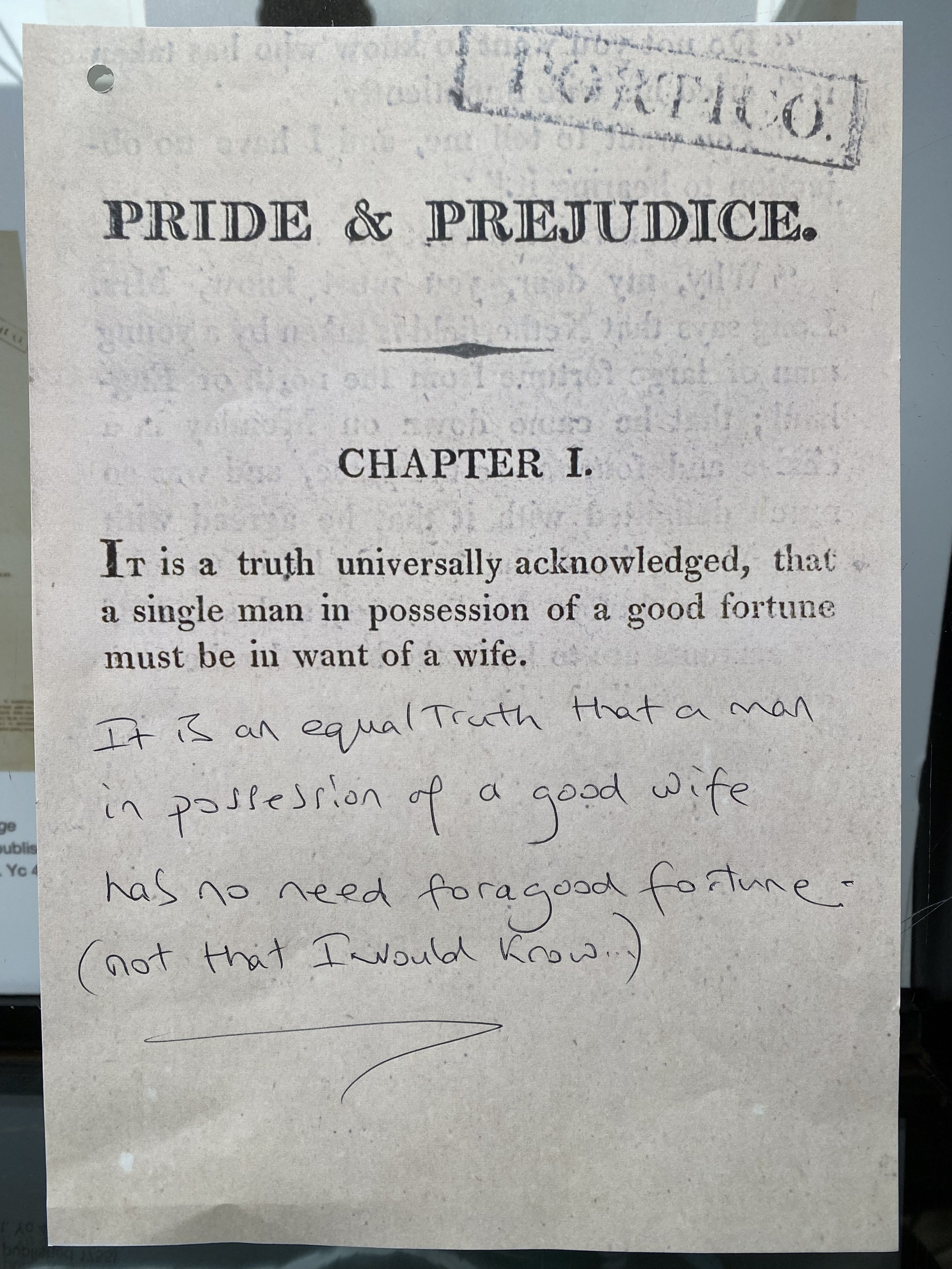

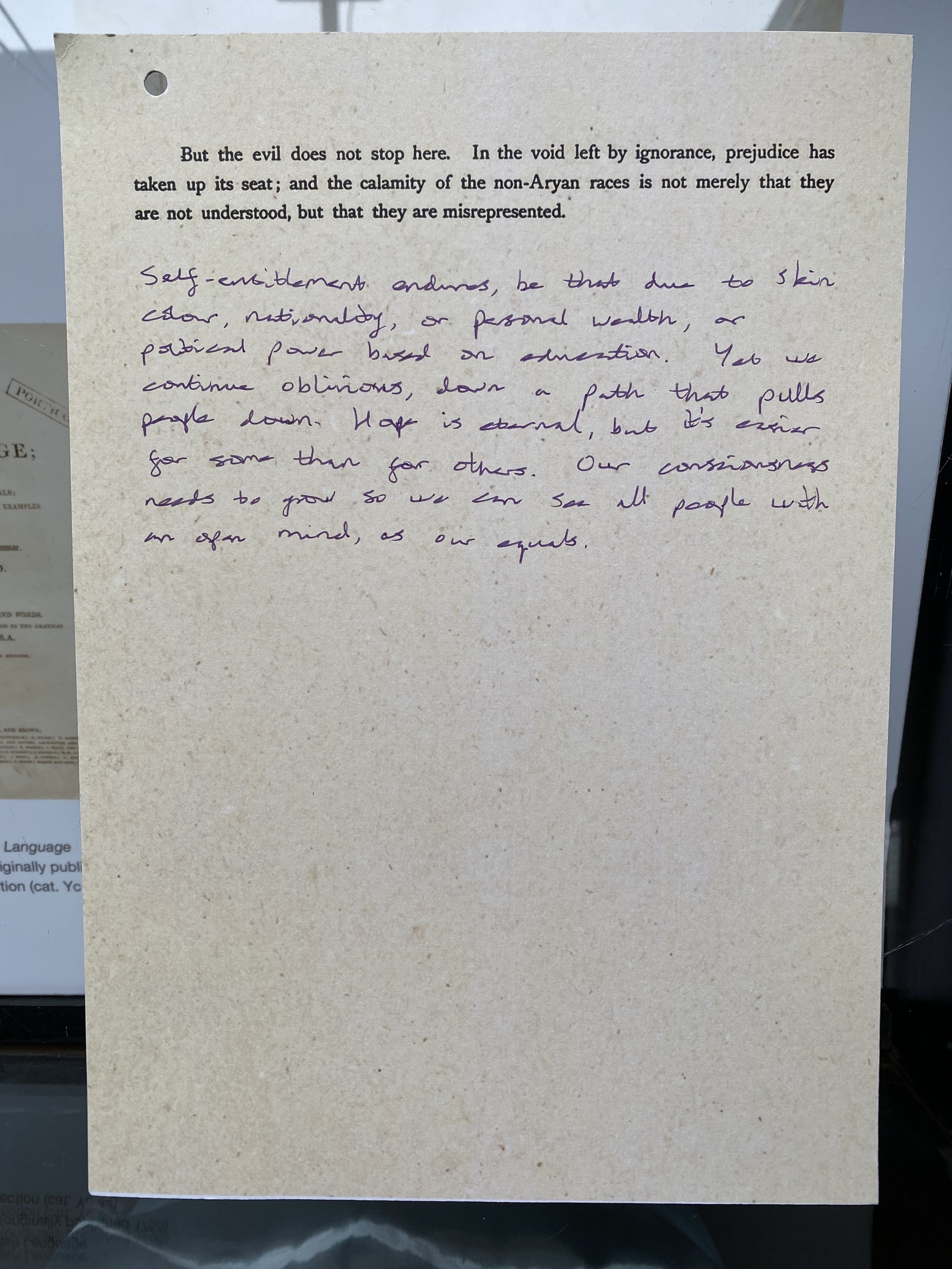

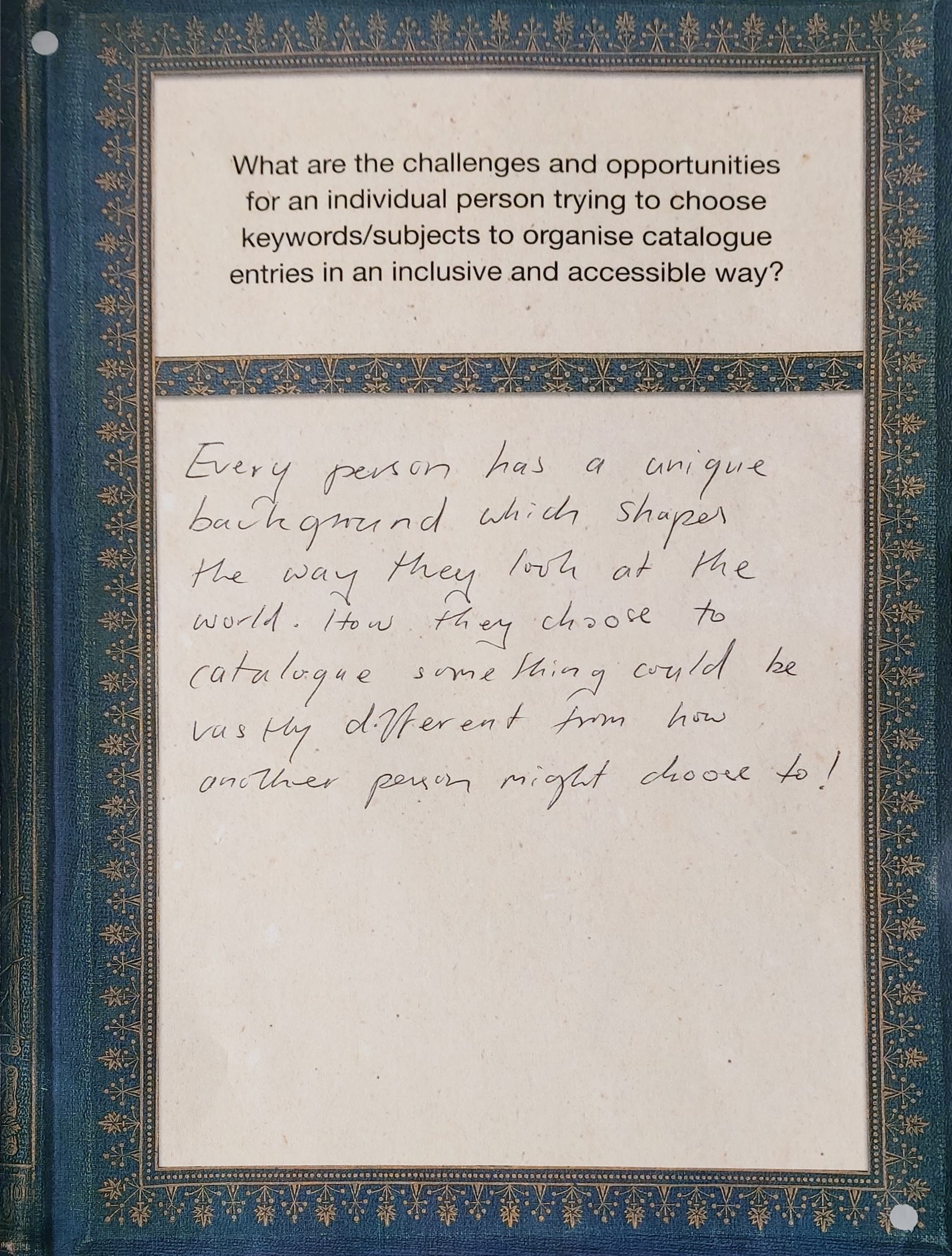

For In the Margins, a group of artists, writers, students, and Manchester residents have come together to challenge the traditionally ‘male, stale, and pale’ reputation of historic libraries by asking: Whose voice is loud enough to be heard? Who are the arbiters of established facts? Through whose eyes do we frame the world?

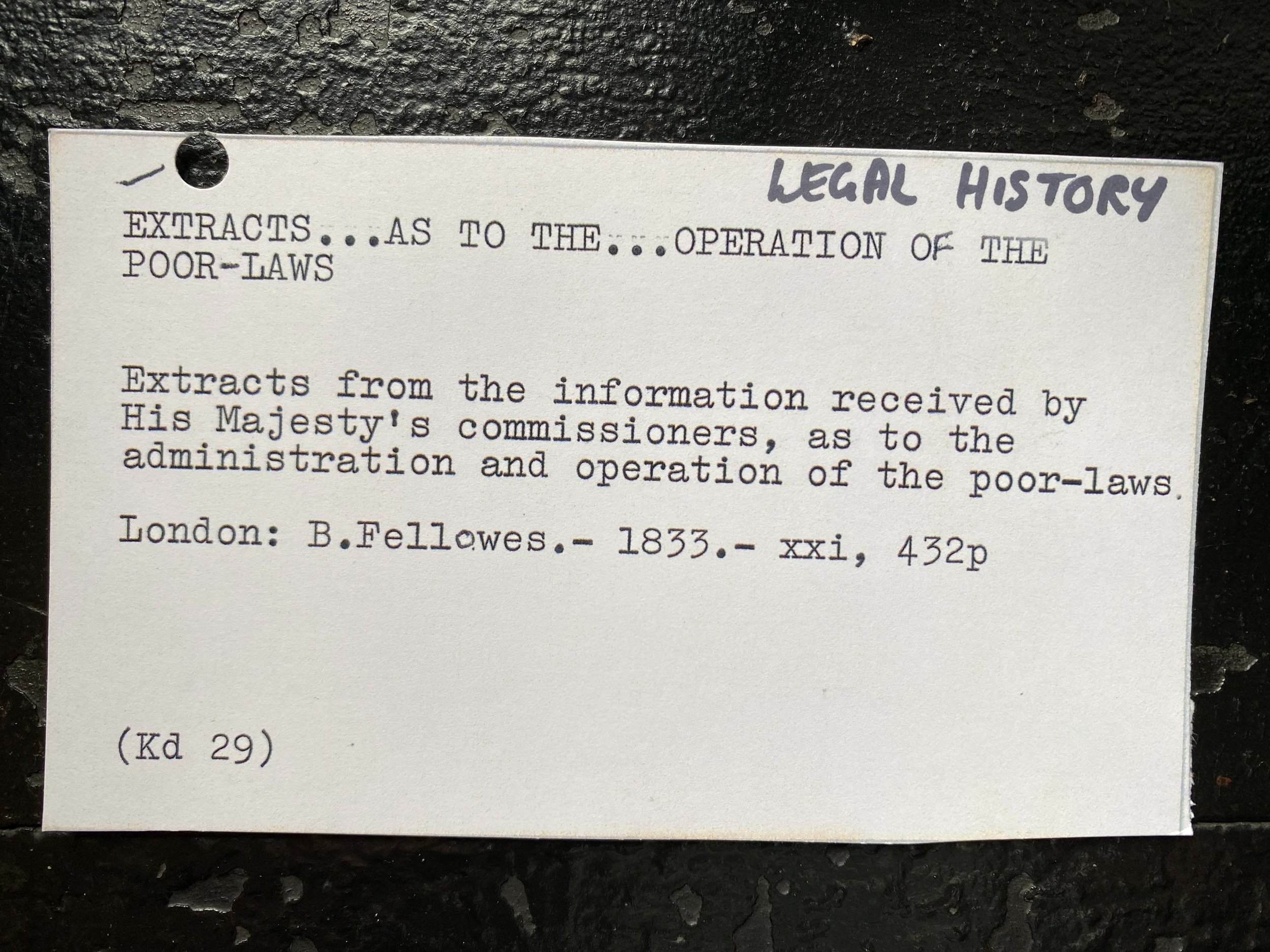

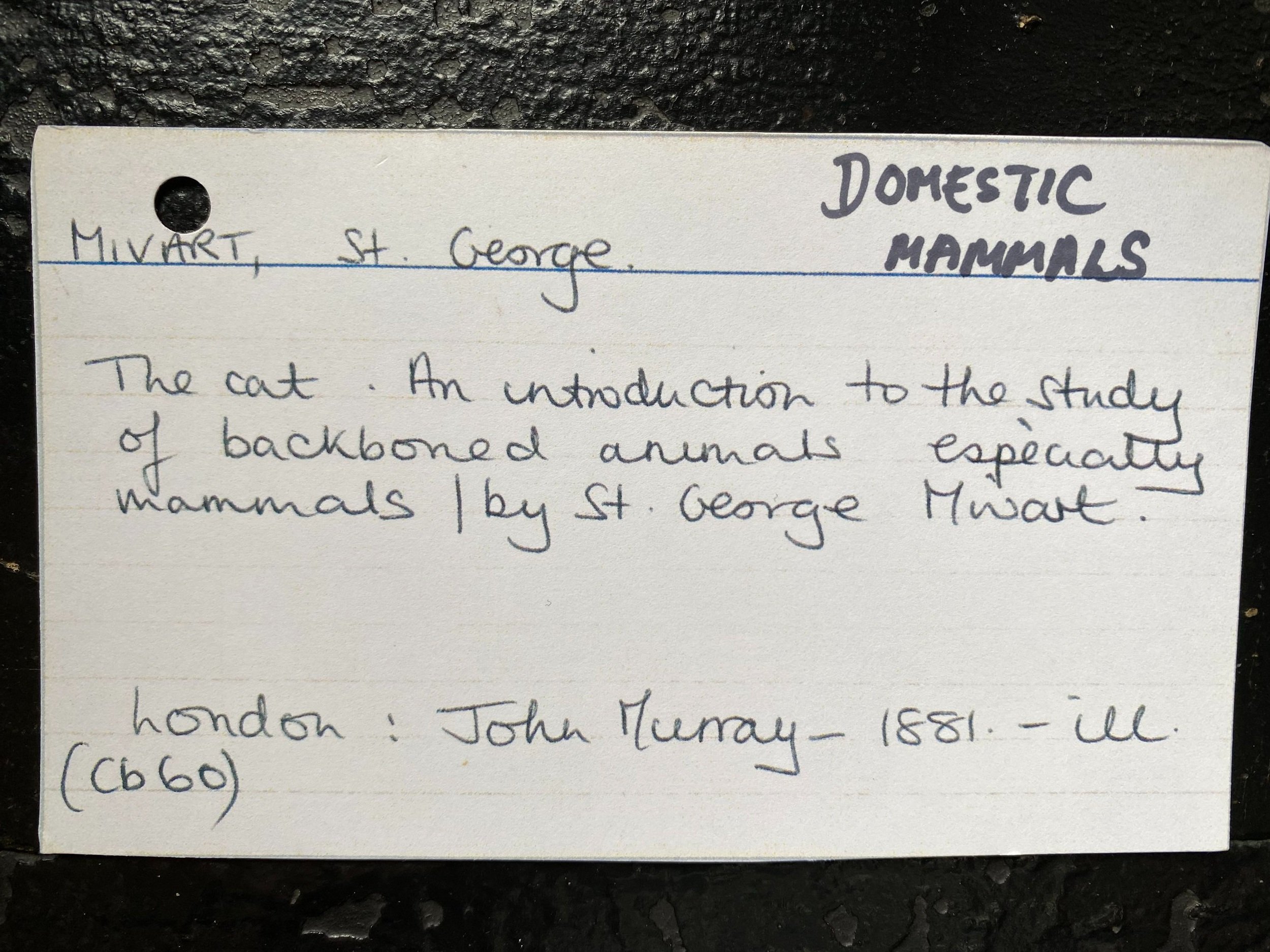

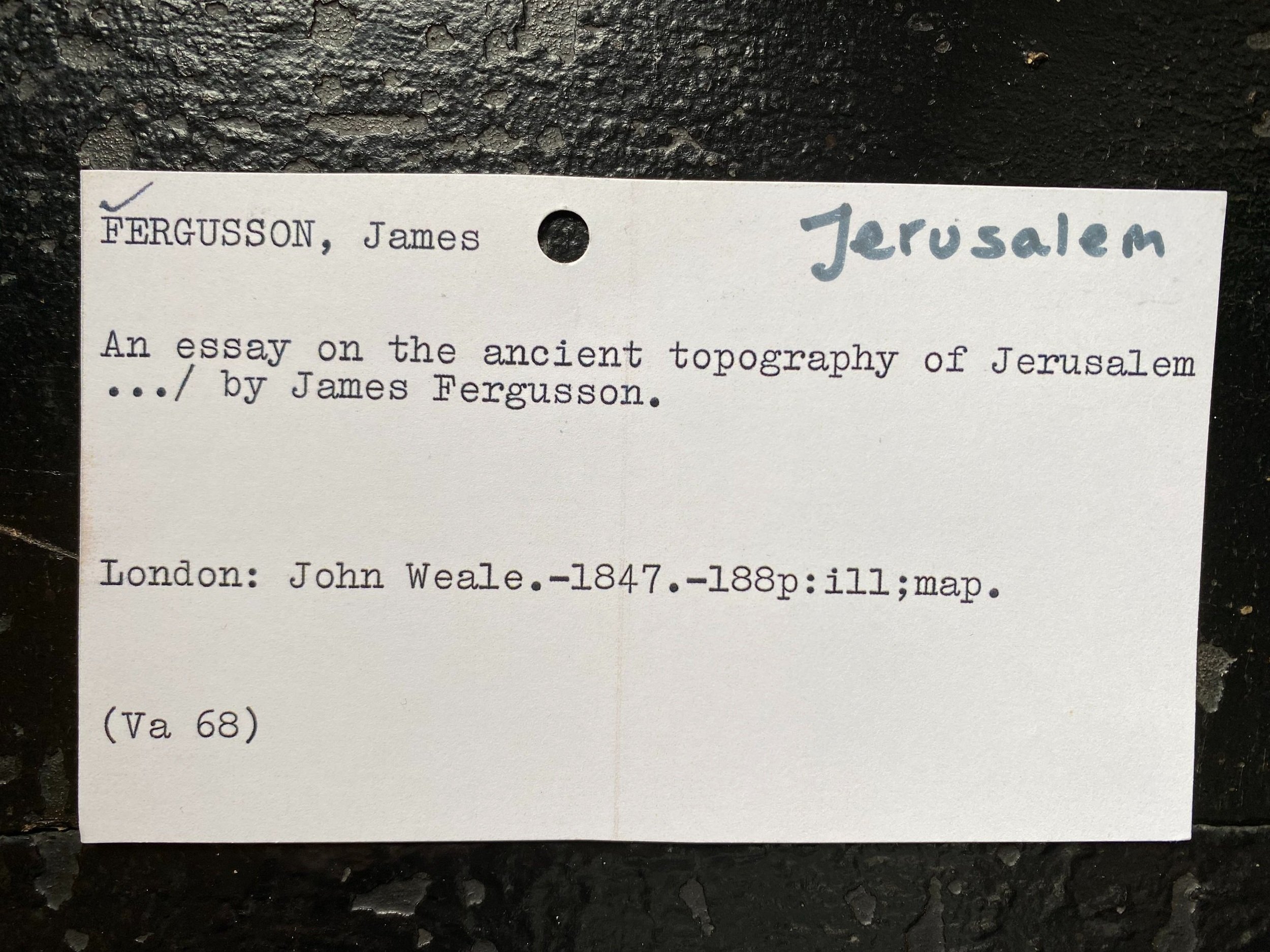

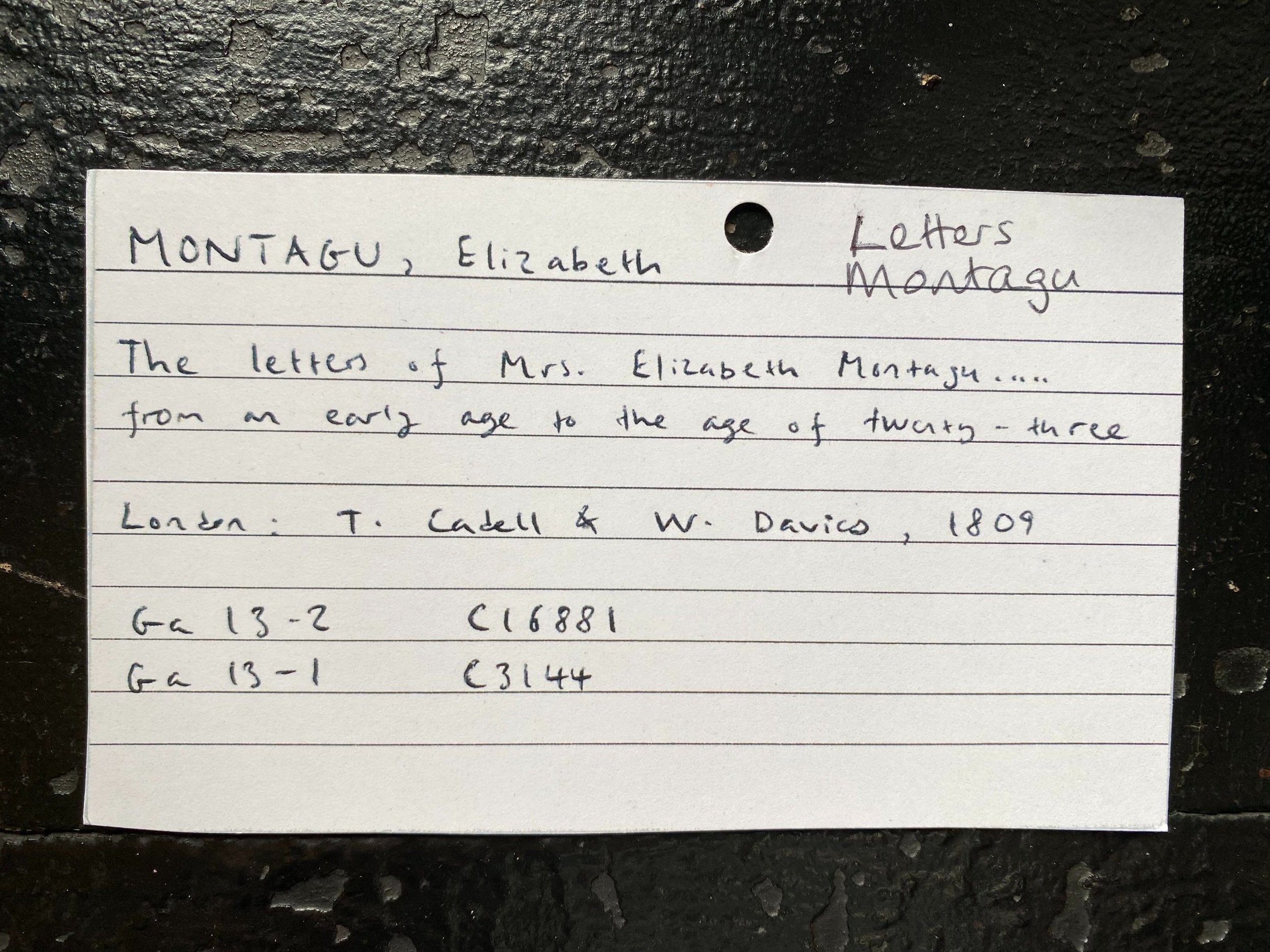

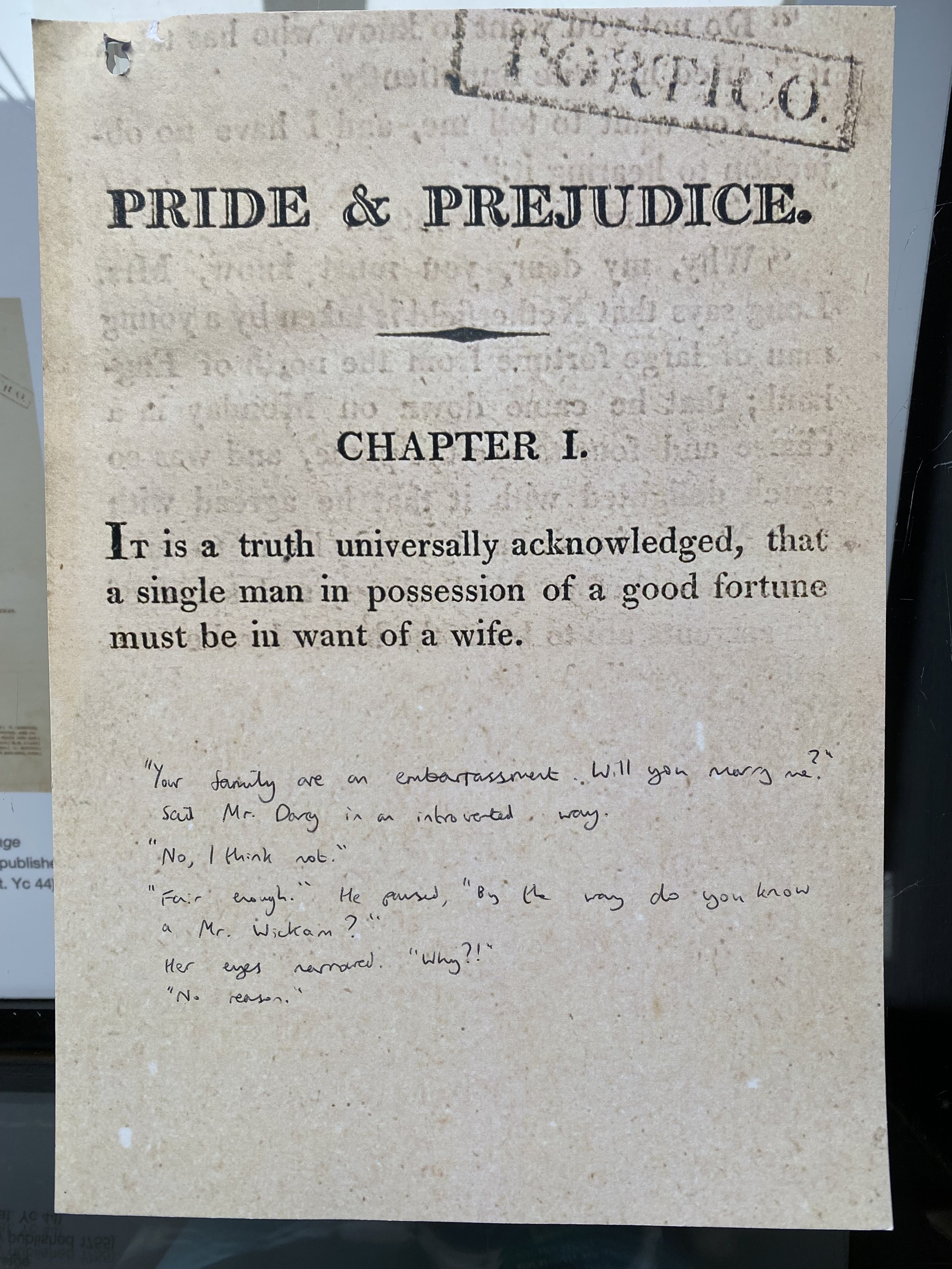

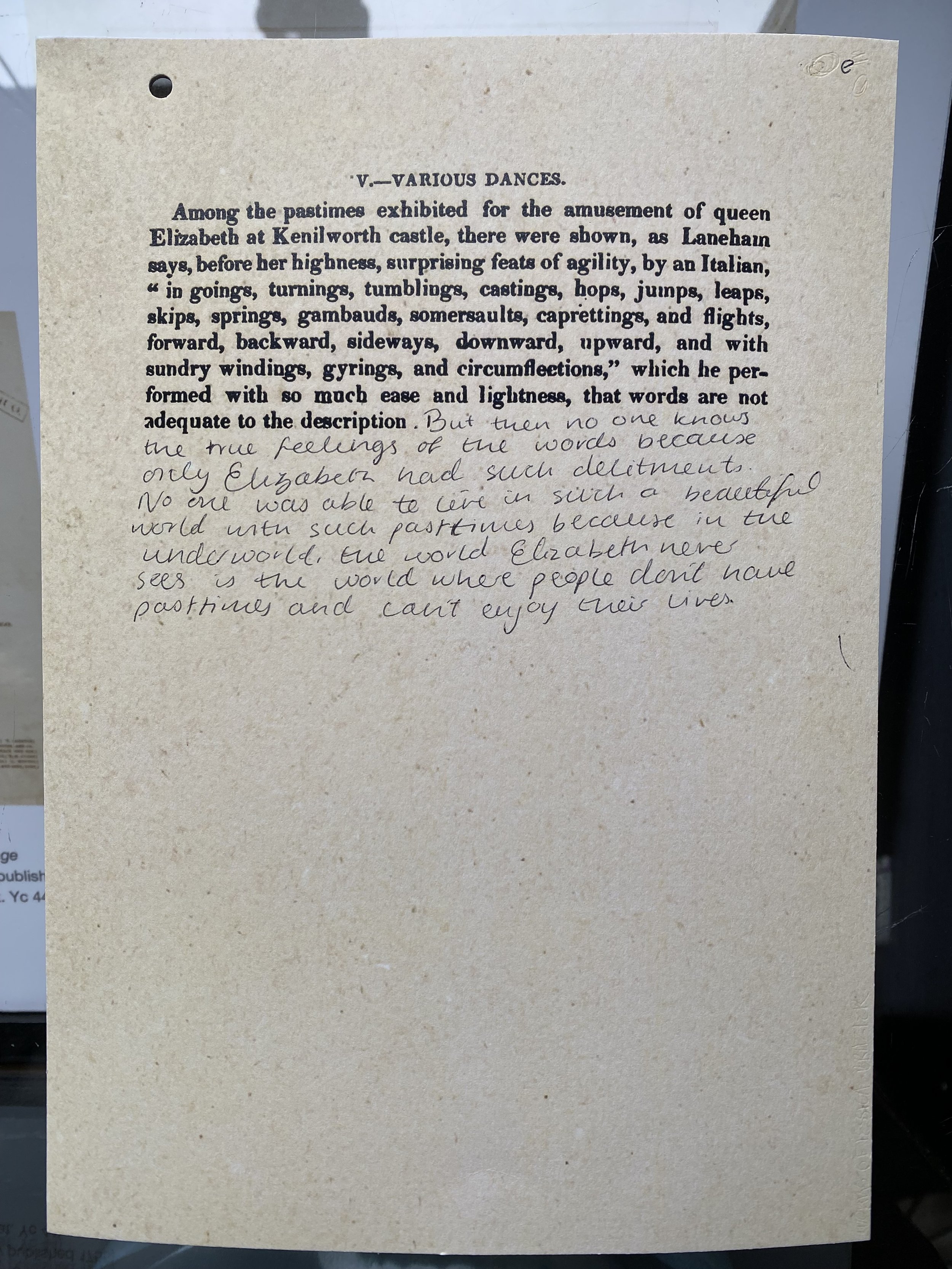

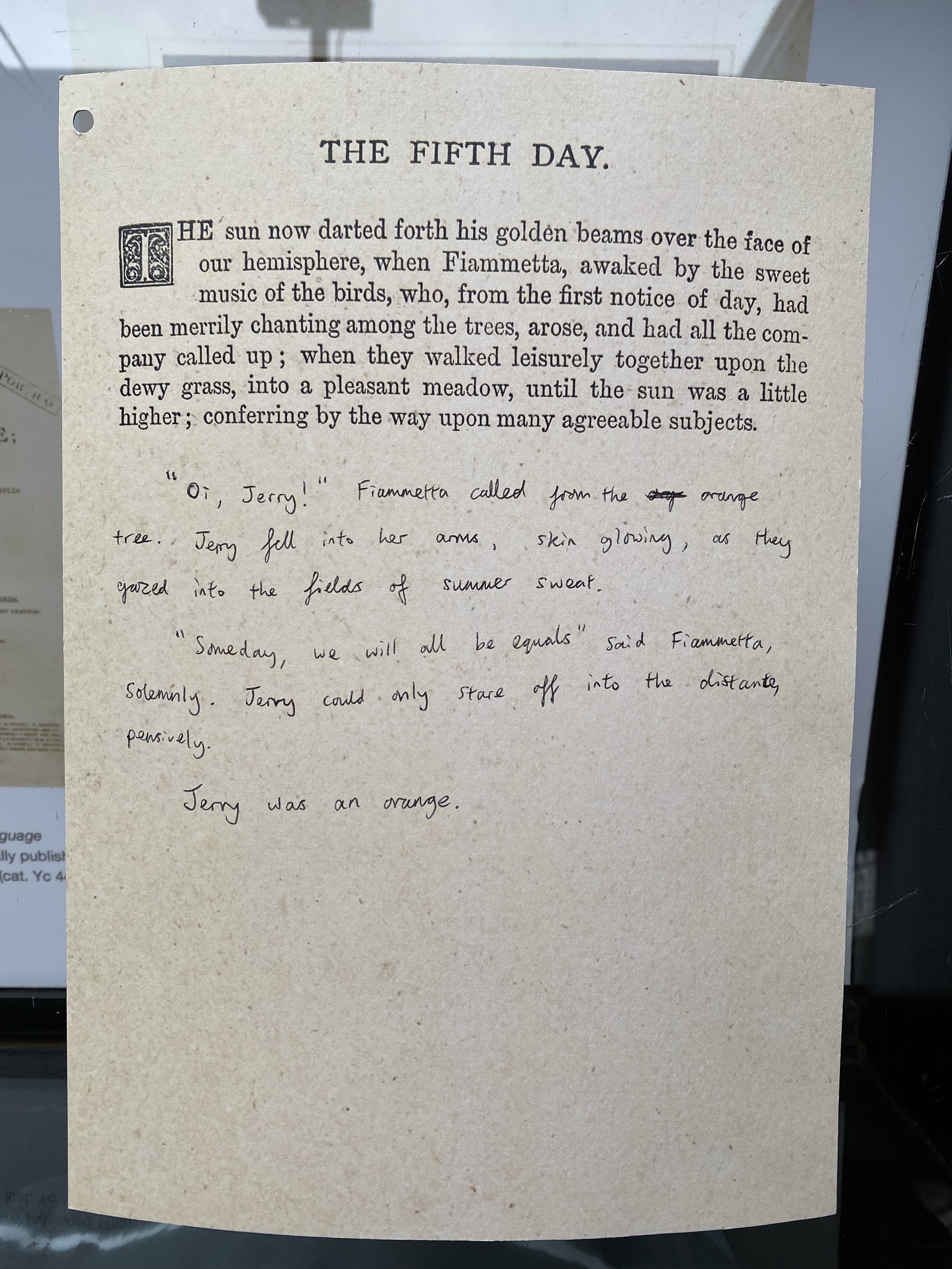

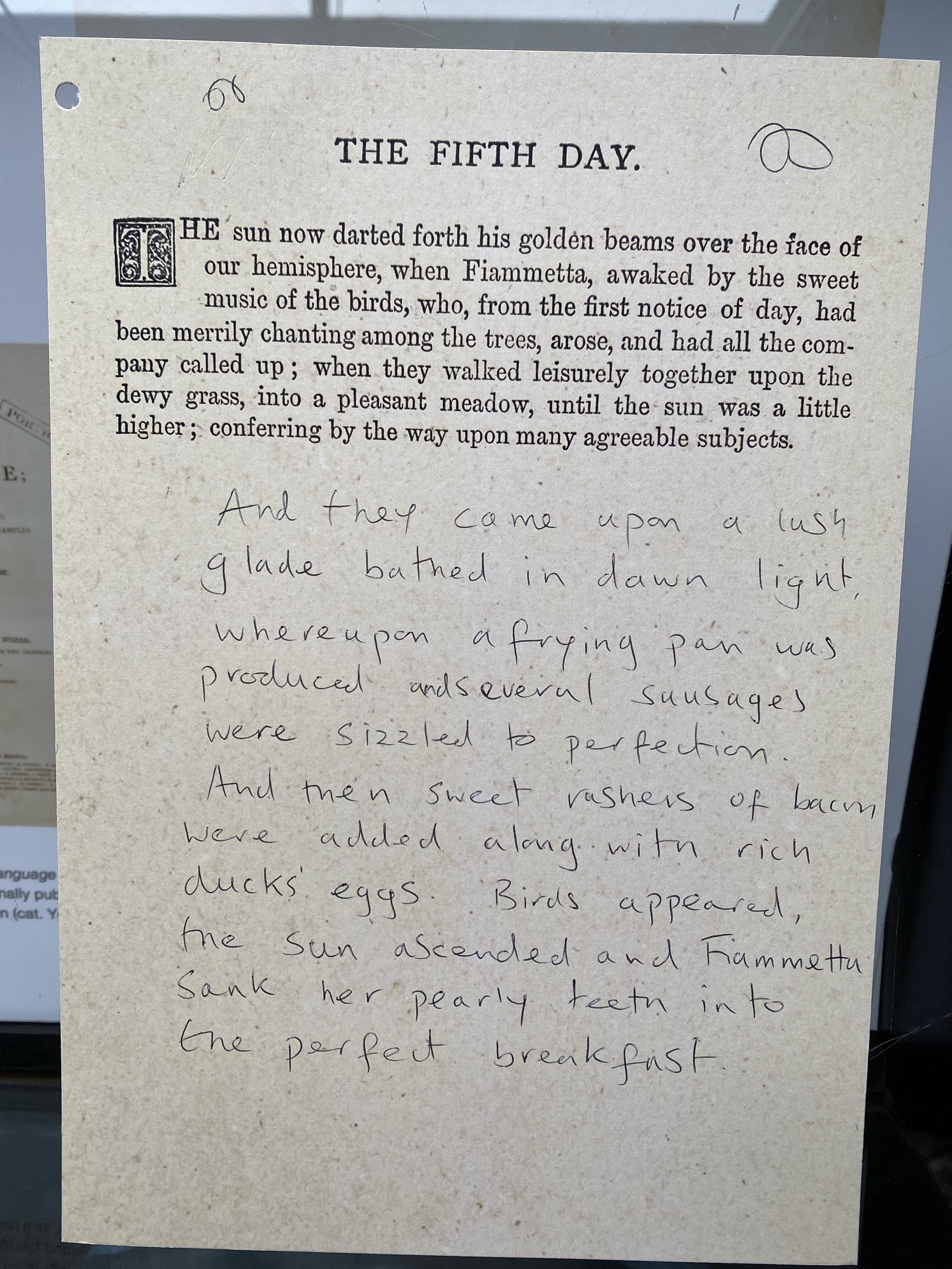

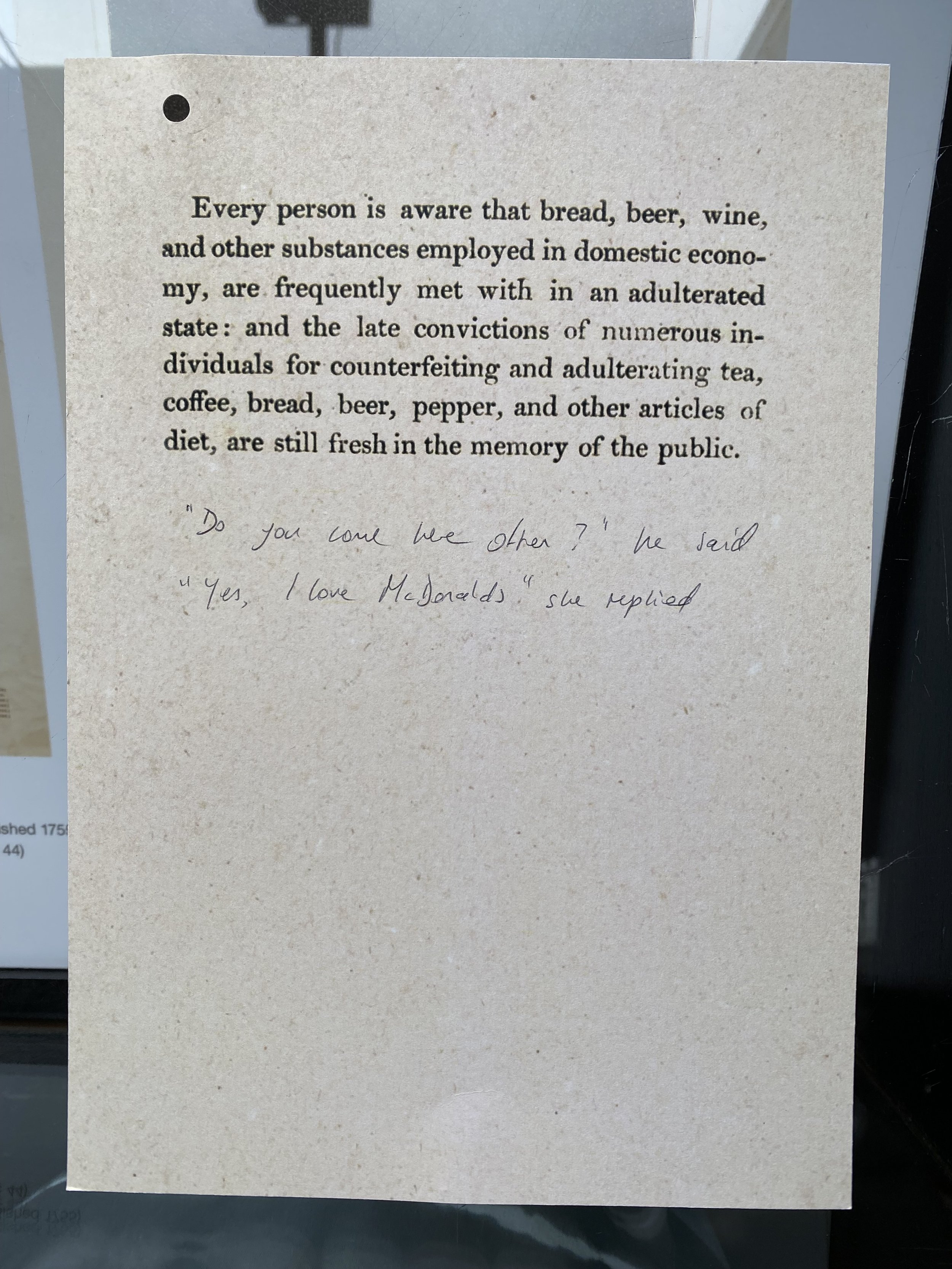

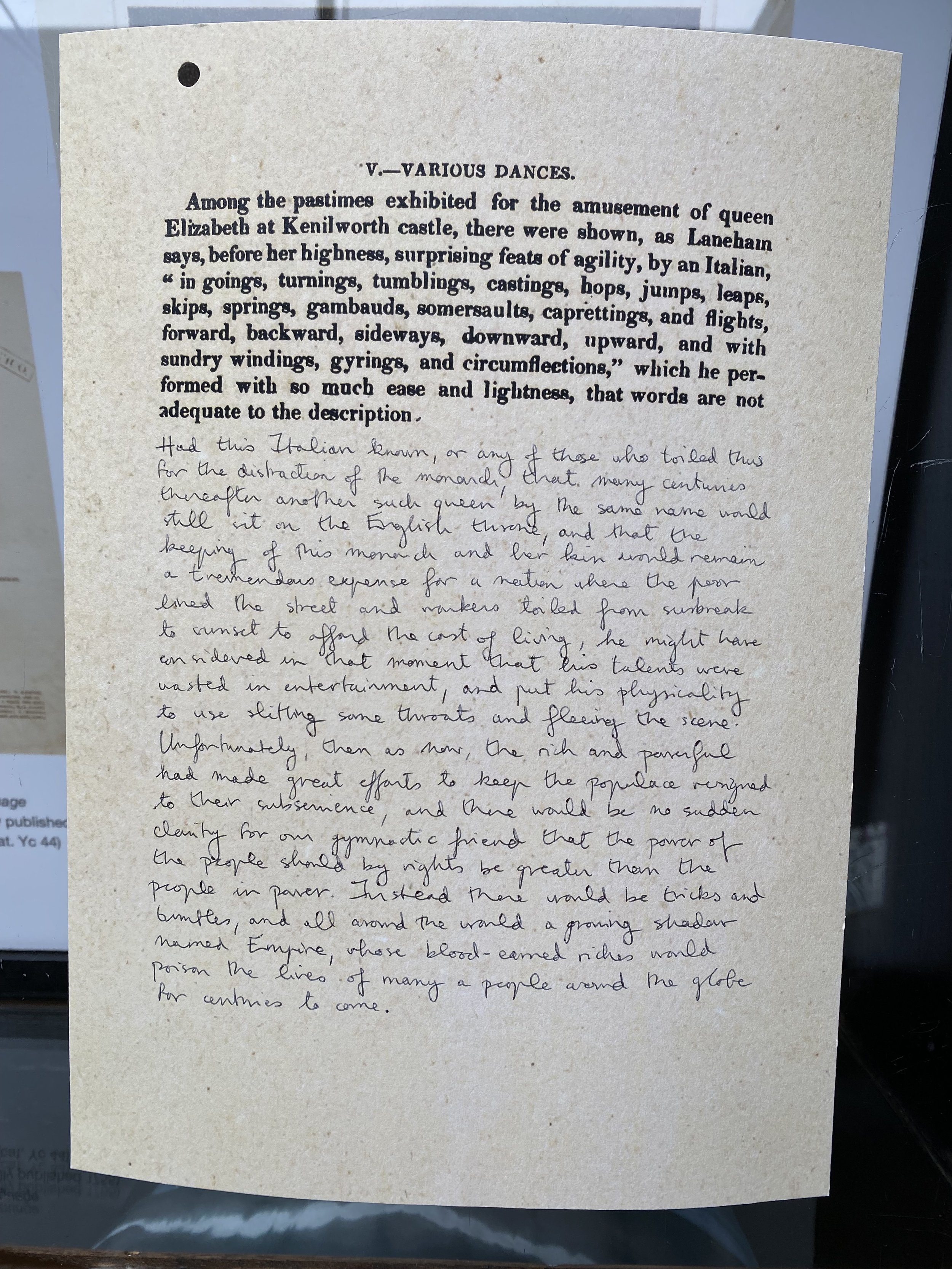

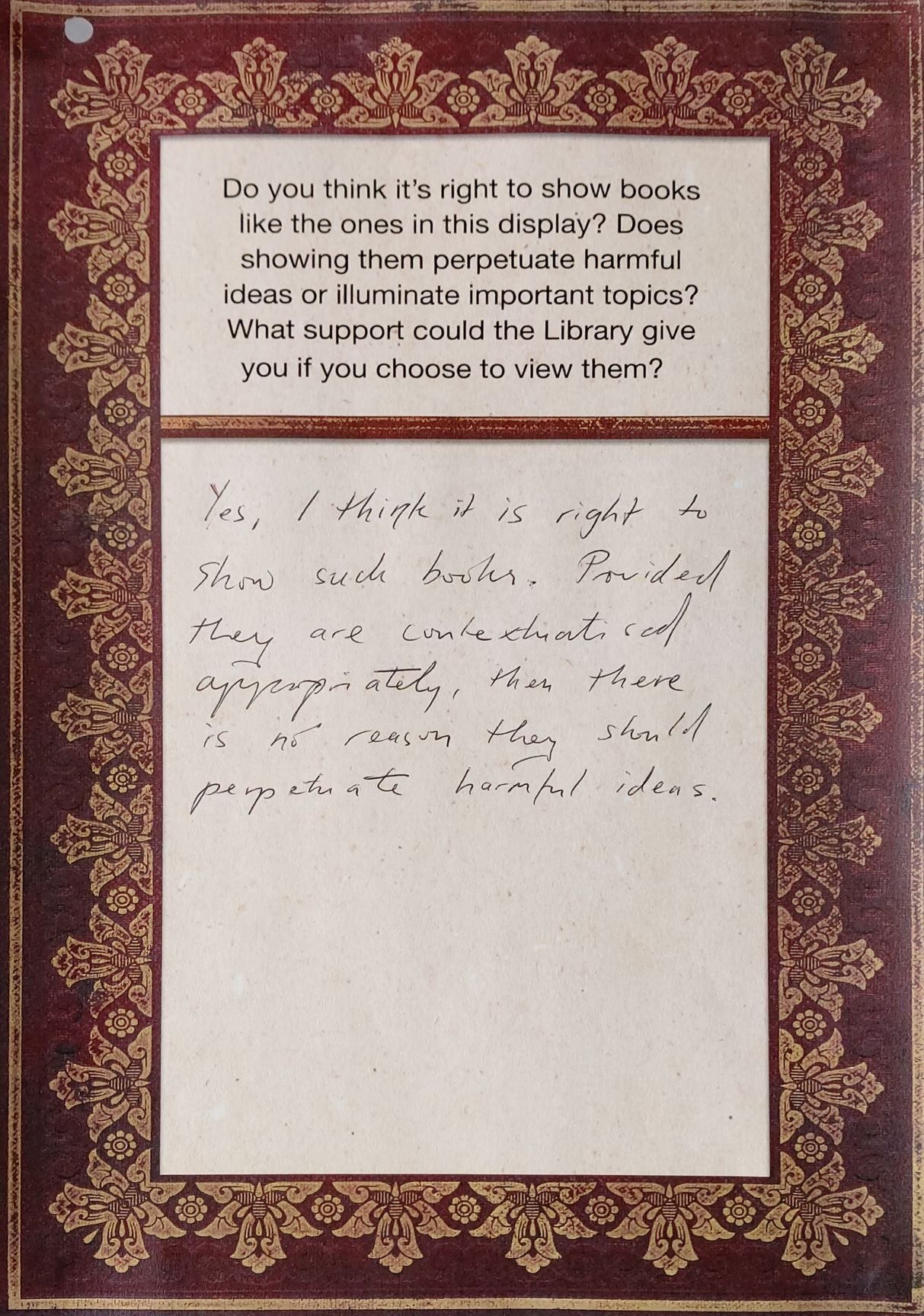

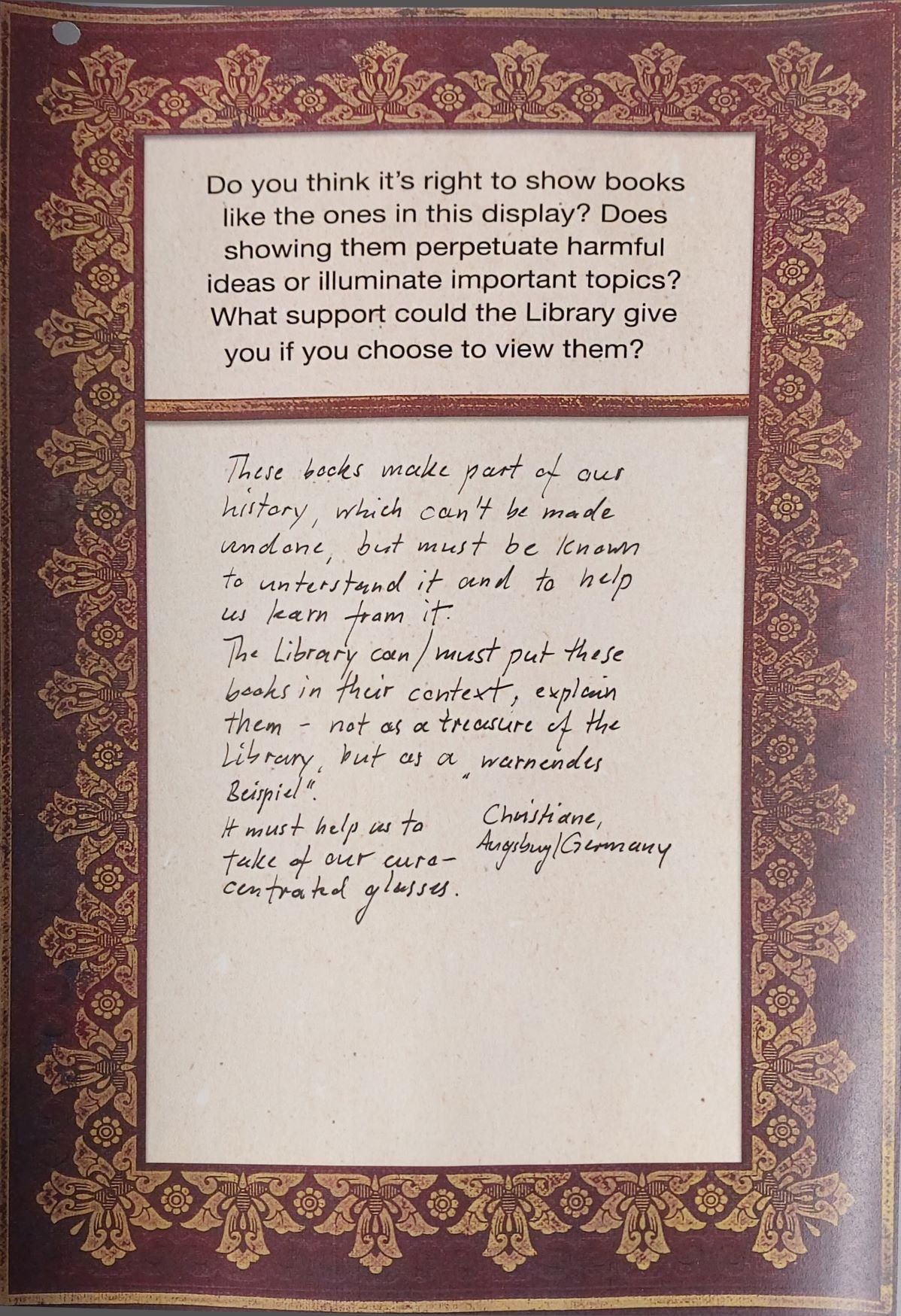

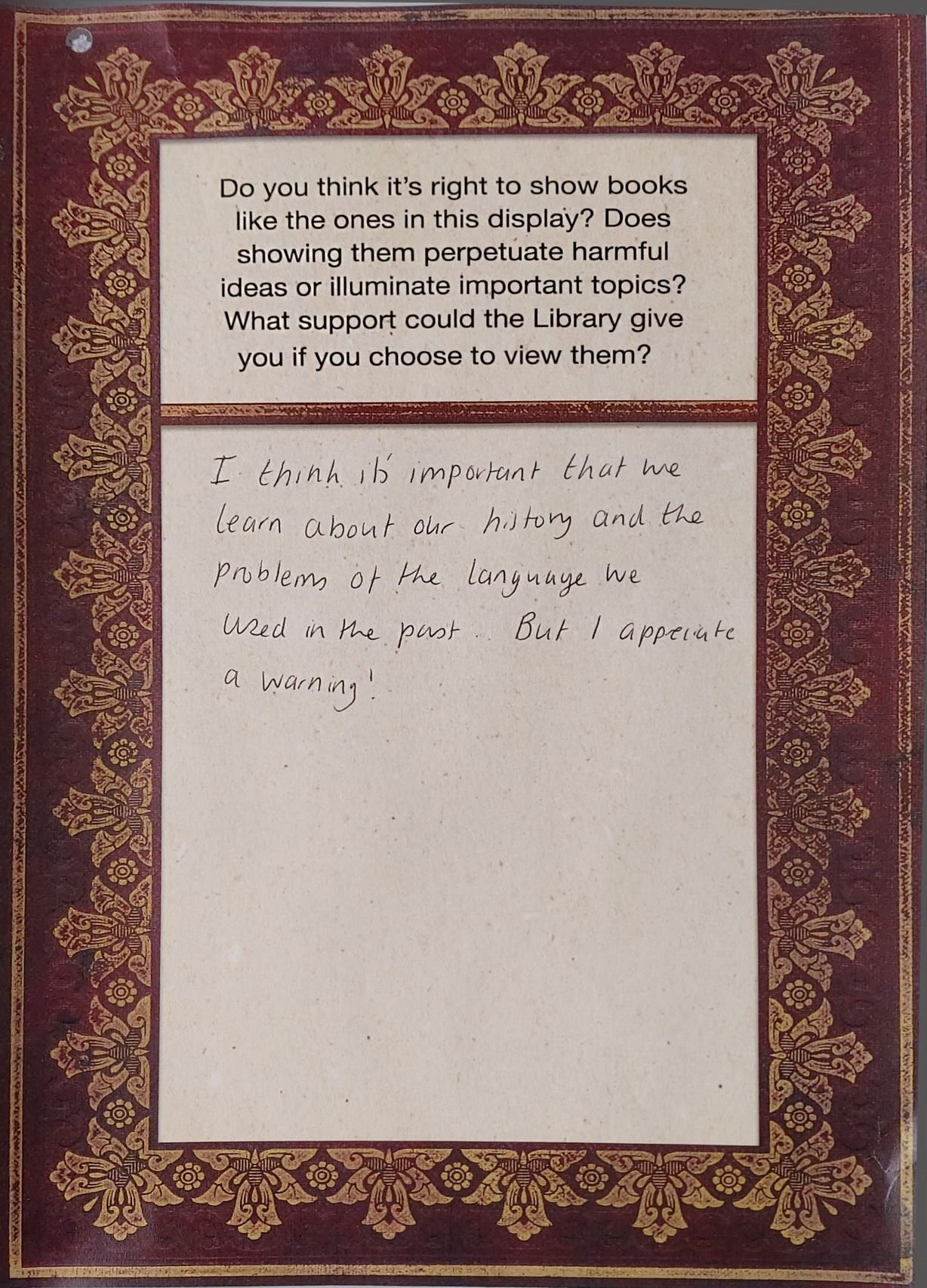

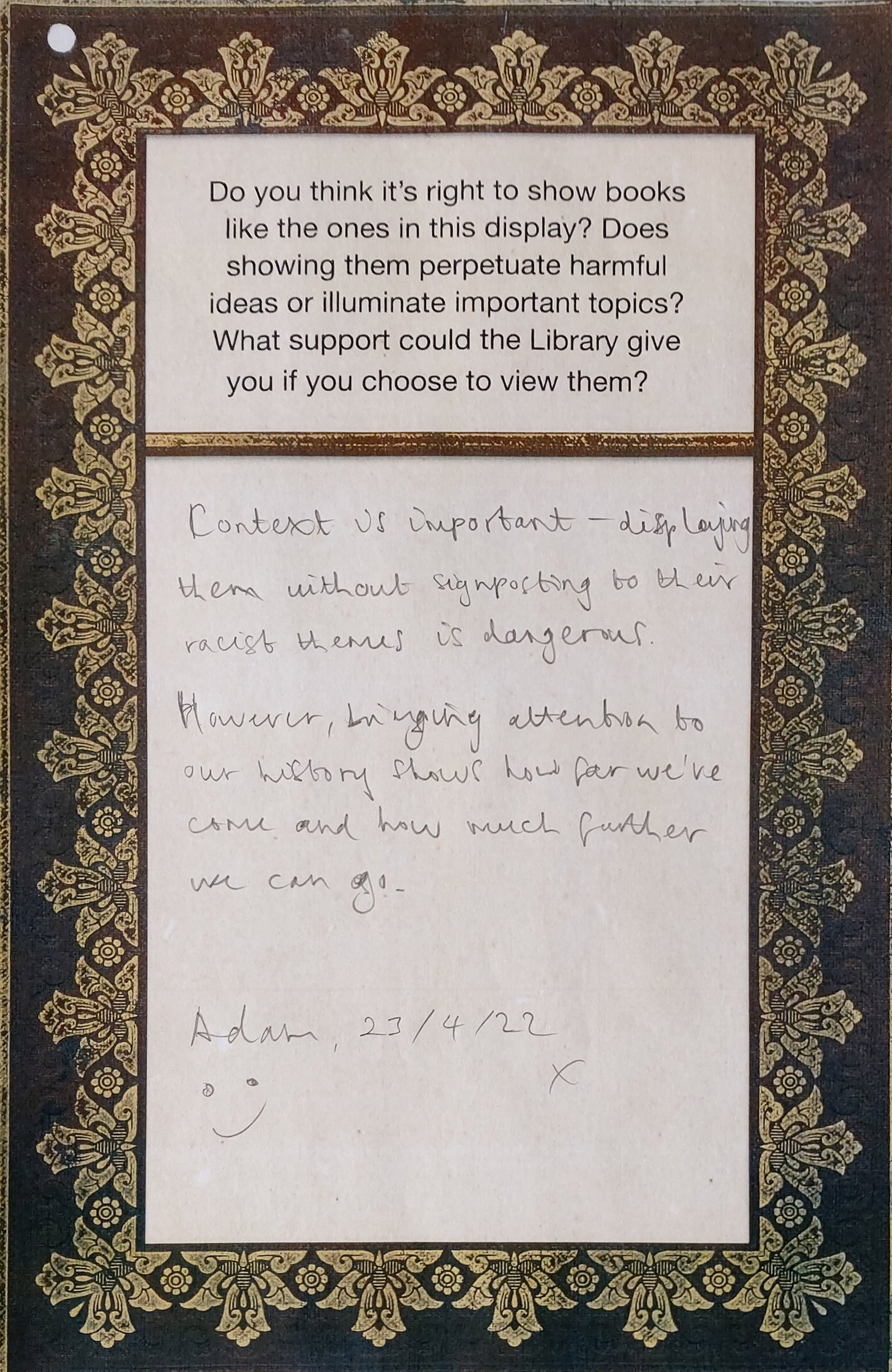

From the obscured and overlooked to the dangerous and disturbing, the Library's eighteenth and nineteenth-century collection reflects the histories of Manchester and the world. But it is what is left unsaid that haunts the texts as they sit so ‘politely’ on these two-hundred-year-old shelves. To choose the books and activities in this display, we have considered what blurs when we focus, what doesn’t make the word count, and what is too-often relegated to the background.

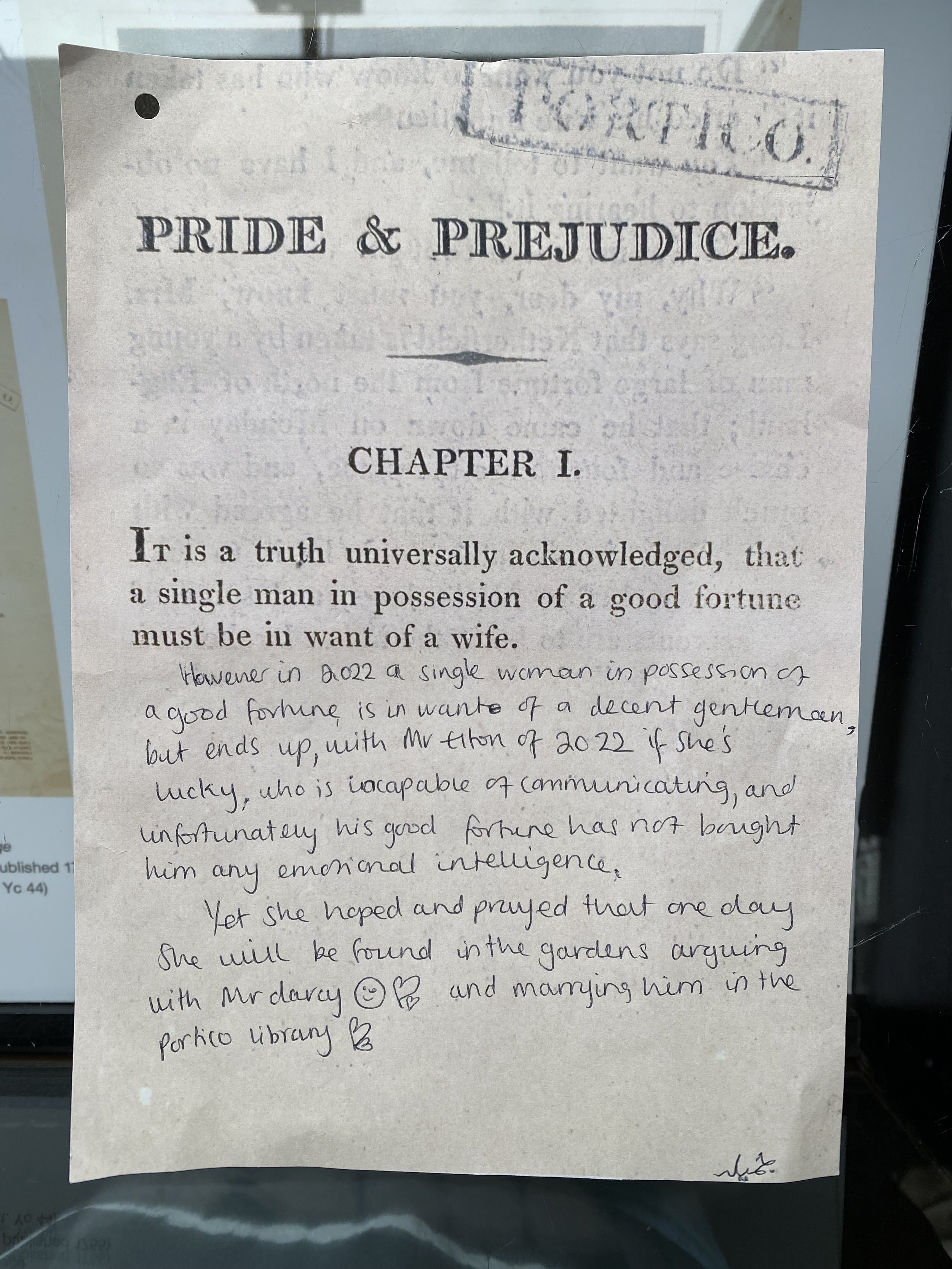

Throughout the year, the Portico hosts exhibitions from local and international artists that examine the historic collection’s influence on twenty-first-century life and society. This summer, we have cleared the display space for you to tell us what these books mean to you, how the city can make the most of this unique resource, and what futures the Library can contribute to.

Between April and June 2022, display materials, images, texts and activities will appear here as the Library’s visitors create them. Bookmark this page and follow our social media to see them, and to add your responses.

In the Margins In the Frame

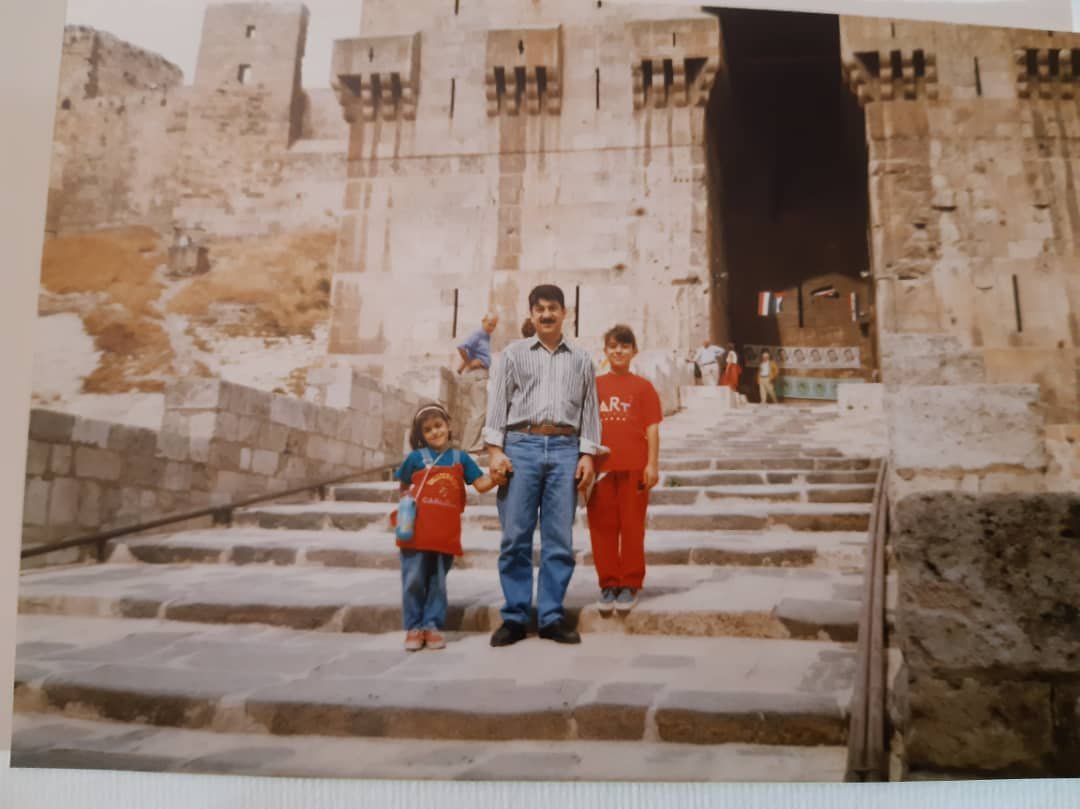

Bring your selfies, snaps of friends and family, or magazine clippings along to the Library and make a collage to add yourself to the gallery.

![“The Boy of the Back of the Class” from Onjali Q. Rauf – it is […] beautiful. And I want that many other people read and hear (?) it. And enjoy it like I did – Joseph.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6063581e3e356f4ceeed1b02/1653945877623-LVGPV9691WCJPDA6IK2P/In+the+Margins+Q_A+responses+%285%29.jpg)

![Present day book: One Minute Around The World In 60 Seconds by Vladimir Arsenijevic and Valentina Brostean. [Consists of] 25 fragments in one minutes of time around the world. Expresses through words and images the immediacy of today’s world a](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6063581e3e356f4ceeed1b02/1653946007746-KSFN681LQMXJSSZMAUFY/In+the+Margins+Q_A+responses+%2815%29.jpg)

![The Rattle Bag [Poetry and Anthology] compiled by Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney. It is an eclectic collection of well known and obscure English poetry put together by two of the greatest ears and voices of the 20th century. ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6063581e3e356f4ceeed1b02/1653946055783-0JCPTAWB5RX23FDD26QF/In+the+Margins+Q_A+responses+%2821%29.jpg)